An excerpt from J.L. Rainey’s Journal, Selma, Alabama, March 1965, from the novel, The Clock Of Life, by Nancy Klann-Moren.

An excerpt from J.L. Rainey’s Journal, Selma, Alabama, March 1965, from the novel, The Clock Of Life, by Nancy Klann-Moren.

My posts will include both J.L.’s journal entries, and actual articles from The Selma Times-Journal each day until he reaches Montgomery.

This is day twenty, the day they finally arrived.

Thu Mar 25―“Make way for the originals!” the marshals shouted through bullhorns, and cordoned us off so the chosen 300 could lead the march. Spam and I were about eight blocks back from the front. The power I felt from being there―what ordinary people can accomplish―will stay with me forever.

When we got into Montgomery proper and marched up Goat Hill, I turned around and looked back. Thousands and thousands of people marched up Dexter Avenue toward the State Capitol Building, at last. Thousands more had lined the streets to watch us pass.

MLK stood on the steps. Couldn’t catch every word, but no one needed to hear perfectly to get the message. HOW LONG WILL IT TAKE? ―HOW LONG? NOT LONG.

At the end of his speech when he raised his hand and yelled “Glory, hallelujah! Glory, hallelujah! Glory hallelujah, His truth is marching on,” both history and fate held my hand.

Drenched in adrenaline, we left right after the speech, caught a ride back to Selma and stayed up talking about it all night.

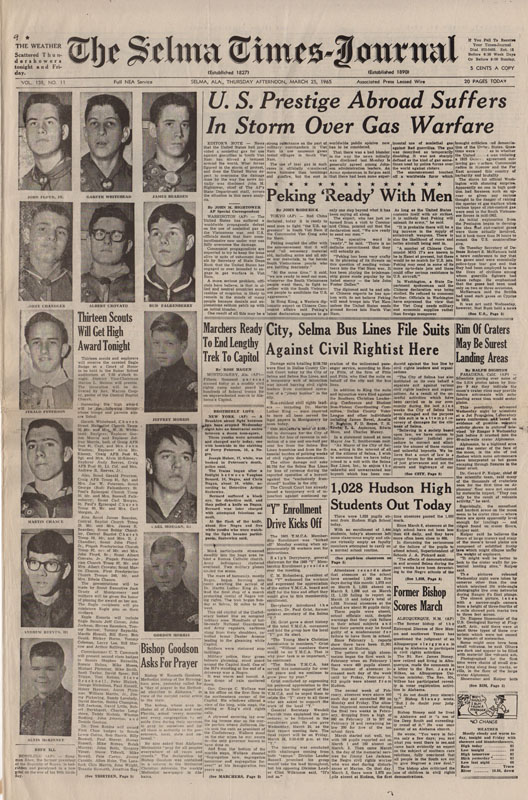

Thursday Afternoon, March 25, 1965 Selma Times-Journal reported:

Marchers Ready to End Lengthy Trek To Capitol by Ross Hagen

Montgomery, Ala (AP) – Fifteen thousand persons massed today at a muddy civil rights camp under guard by hundreds of federal troops for an unprecedented march to Alabama’s Capital. More participants streamed steadily into the huge area behind a Roman Catholic church. Army helicopters clattered overhead. Two military planes circled the scene.

The mass of humanity, mostly Negro, began forming into ranks awaiting the arrival of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to lead at he final step of a march protesting denial of Negro voting rights. The trek began Sunday at Selma, 50 miles to the west.

The old capital of the Confederacy looked like an occupied military zone. Hundreds of battle-ready National Guardsmen and Army regulars, carbines slung from their shoulders, patrolled broad Dexter Avenue leading to the gleaming white Capitol. Soldiers were stationed atop the buildings. Military police, their green helmets gleaming, stood guard around the Capitol itself. One of the MP’s standing at the end of a driveway was a Negro.

It was warm and humid. A few drops of rain spattered down.

Gov. George C. Wallace was in his office on the first floor in the northeastern corner of the Capitol. His windows offered a view of the long, wide steps, the setting for King’s civil rights rally.

A plywood covering lay over the big bronze star on the marble portico where Jefferson Davis took the oath as president of the Confederacy. Wallace stood on the star when he was sworn in – the only governor known to have done so. And from the bottom of the marble steps, Wallace shouted “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow and segregation for ever!” at his inauguration two years ago.

An aid to the governor said the portico was covered only to protect the marble, but an unidentified state trooper said it was covered to prevent King from standing on the historic star.

Flying from the top of the white dome was the Alabama State flag. Below it was the Confederate flag. The U.S. flag fluttered from its own staff on the green, flower-ringed south lawn facing the first White House of the Confederacy. Two old blackened Civil War cannons jutted out from the sides of the Capitol steps. A statue of Jefferson Davis stood near the entrance.

A few state employees stood on the steps. They watched a construction crew building a speakers platform on a truck bed in the street. A dead skunk lay in the street about a half-block away. Women employees of the state took the day off. This brought a virtual breakdown to the legislature’s work since there were no clerks. Officials decided to give the women the day off because of the march.